In football, some names are larger than life, with tales of their feats having been passed down over the years. However, quite often there’s more to their stories than what that old bloke chewing your ear at the bar shared with you. Often there’s a ripper yarn to accompany that name that you’ve never really heard of, or an unknown chapter in the life of the legend you hear so much about. Any Given Mongrel delves into those yarns, characters, legends and their stories.

Each generation there’s a player or two whose list of accomplishments in life and career are the envy of their peers. They are the kind of players who not only rack up records and accolades on the field, but continue their hard work, dedication and determination once the game has passed them. Their names and legacies are regarded as legendary; a word that is toyed with far too frequently in today’s media, but loses absolutely no sentiment in the case of this legend.

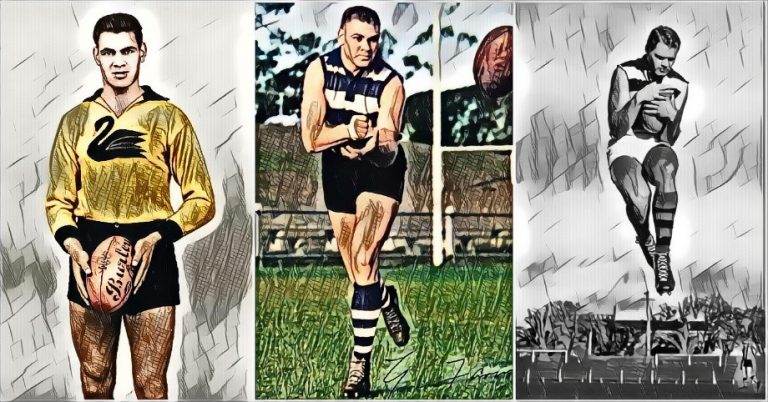

A name that’s synonymous with terms like; trailblazer, revolutionary, groundbreaking and extraordinary, all traits that helped earn his place as one of the 12 players selected as inaugural legends in the AFL Hall Of Fame in 1996, is none other than Graham ‘Polly’ Farmer. Highly distinguished and eternally respected, the life and legacy of Farmer is one of achievement and overcoming the odds.

A member of the Stolen Generation, born in North Fremantle in 1935 to an unmarried, twenty-five-year old Noongar mother and an unknown father, at just 18 months of age Graham Vivian Farmer was left in the care of an orphanage for aboriginal children run by Protestant Nun; Sister Kate.

History tells us that most would experience great horrors and terrible upbringings in circumstances such as this, however Farmer was forever thankful for his time at Sister Kate’s. He always appreciated the care he received in his early life. Perhaps the most prominent legacy of his that he carried from his youth was his perpetual nickname “Polly”, bestowed upon him around the age of 6 for his reputation of constantly chattering away like a parrot – a strange sentiment for one to look back on, especially considering Farmer was renowned as a quiet, seldom spoken man for the majority of his career and adult life.

Childhood friend and fellow resident from Sister Kate’s, Ted ‘Square’ Kilmurray once said “opposition boys would say, we can’t play footy against you blokes, cause you haven’t got any footy boots. But that was alright because they couldn’t catch us anyways”.

“If it had not been for Sister Kate’s, I would have had an ice block’s hope in hell of ever leading a normal life. I owe her and all her dedicated helpers everything – for giving me the chance to make something of myself. I was one of the lucky ones.” – Polly Farmer 2005

The next thirteen years of his life were spent in the care of Sister Kate’s where he was first introduced to football and other sports along with his fellow children, despite never owning a pair of shoes. It wasn’t until age 14 when he moved to Greenbushes, a mining and timber town in South Western W.A. that he received his first shoe; a single left shoe. Would this small feat become the precursor to his penetrating left foot that he favoured his entire career? It was symbolic enough for Polly himself to blame for his one leg being shorter than the other in later years. Medical science however, disagrees. A severe bout of Polio as a teenager was more likely the cause of his uneven leg size, and subsequent subtle limp that he carried his entire life.

The dream of all young boys to play football at the highest level came in his high school years. Such a dream however, may not have come to fruition had archaic governmental policies of the Western Australian Nature Welfare Department been upheld. In that time, it was mandatory that aboriginal youth be sent to work the land on farms and in the countryside upon turning 16. With thanks to The Sunday Times of Perth, in 1952 Farmer was granted an exemption from the state department and was allowed to stay in Perth. By using his name and image to front a petition, the newspaper was successful in gaining the support of the public and having the decision overturned by the governing body. In later years his biography would read; “The only thing I did not want to be doing was farming.”

Initially training and playing for Kennick Football Club, then East Perth at age 18, it took until his second season for Polly to hit his straps and find a regular place in the team. He would go on to play 176 games between 1953 and 1961. In this time he would win seven club best and fairest awards, three premierships in 1956, 1958 and 1959 as well as becoming a three-time Sandover Medalist as the best and fairest player in the WAFL. In 1956 Farmer was chosen to represent the state at the Perth Carnival where he would be awarded the Simpson Medal in their win over South Australia, and adjudged best at the carnival overall to be presented with the Tassie Medal. 1959 and 1961 saw him awarded with another two Simpson Medals for being best on ground in a grand final, and best on ground against Victoria alike.

Humble, shy and reserved, Polly won the hearts of the supporters and caught the eye of interstate recruiters. In 1955 Richmond Football Club signed Farmer for a fee of £200. Agreeing to move to Victoria with a dream of making his mark in the VFL, his vision was blocked as East Perth refused to allow his release, such was common back then. Just another ‘what-if’ for the Tigers faithful to ponder. What could’ve become of the mid-50s Richmond team had they managed to snare the sublime ruck skills and aerial prowess of a raw, yet somewhat composed, big man that would inevitably become a juggernaut of Victorian football?

Punt Road wasn’t the only facility desperate to have Polly grace their lineup, St. Kilda and Geelong were also in constant talks with the agile ruckman. The end of the 1961 season would see Farmer’s contract with East Perth expire. Now with a decision to be made, Polly was adamant that he harboured no desire to move to Victoria and join a ‘top-four’ club. Instead, he started seeking out a club that had the potential foundations to be a winning side – one that he could help escalate into the top-four.

He notified his club that he would be playing for Geelong under then-coach Bob Davis. East Perth were more than happy to allow Farmer’s clearance to play for Geelong, for a fee of £2,000. It was an unprecedented amount for such a cause in those days. Davis recalled eagerly reminding Farmer that he wouldn’t regret his decision, and that his own annual salary was lucky to be that of £800. After friendly negotiation and some quick thinking to come up with the money, Davis reportedly managed to pay £1,500 to appease East Fremantle, and have Polly on his way to the VFL. For real this time!

When asked by Davis how much it would cost them to have him play at Kardinia, much to the delight of the coach, Farmer hastily requested £1,000 for the season. Upon moving to Victoria, Polly soon realised he had undercut himself substantially and was soon to balk, insisting that he had actually meant £1,000 on top of what he would usually get, plus accommodation and other living allowances. The cost of importing a player from interstate was nothing compared to what Bob Davis and others at Geelong envisioned they would receive as return for their investment, and what a return they would receive.

Make no mistake, Ablett was good, but he wasn’t as good as the old G.F. – John Watts (Former Teammate)

Those that remember the time likened the media hype of Graham Polly Farmer’s arrival in Victoria to that of The Beatles arrival. Well, maybe not quite that fanatic, but he was received with great fanfare, that’s for sure. Still in an era where importing interstate players was seen as taboo and an enormous financial risk that most clubs weren’t willing to take, Geelong never shirked the spotlight directed at them from the press. They loved the extra attention that their new superstar recruit was receiving, and were hoping he would be the final piece to their elusive premiership puzzle.

As fate would have it, Geelong would have to wait another season to win their next premiership as disaster struck the club. In his first game for the Cats, Farmer went to ground clutching his knee, sustaining ACL and cartilage damage. After attempting to play another four games, the pin was pulled on his season as he battled to walk to and from a ruck contest. Knocking the wind out of Geelong’s sails, they would have to wait another season to see their boom recruit repay the club’s faith in him.

As 1963 rolled around, you could almost be forgiven for thinking that the fate of the season was written by a Geelong tragic, such was the trajectory of their success. Not only did Farmer help guide them to a premiership, he won their best and fairest, polled a close second in the Brownlow Medal to winner Bob Skilton, and went on to represent Victoria. He would go on to win the best and fairest in the following season, and captain Geelong for three years.

Farmer’s football philosophy was simple – play team football and keep the ball moving at all costs. To talk about the technique of Farmer in the ruck would be like consulting words carved in the stones of a bygone era. The fact that he was first choice ruckman in the AFL Team of the Century, the Geelong Team of the Century, the Indigenous Team of the Century, West Perth Team of the Century and the East Perth Team of the Century says something about the legacy he left on the game. Not only in the ruck department, but in the way we still play the game to this day.

Being his direct understudy for four seasons, Sam Newman still marvels at how Farmer turned such unconventional methods of ruck science for his day, into some that are still the norm in today’s modern take on the game. Early on, he was known to jump a little late, utilising his height and athleticism, using the same side leg to launch off, as the hand he would use to tap the ball. After his knee injury in 1962 however, he adopted an earlier jump. In doing this he was able to drive his other knee into his opponent and get a second lift off his opposing ruckman’s body.

“He was my inspiration, my hero. I attribute everything I learnt and achieved in football to playing in a team with that man.” – John ‘Sam’ Newman. (Former teammate and close friend)

Brownlow Medallist, Gary Dempsey was always in awe of the way such a big player could manipulate the entire play before he had even touched the ball. He was a rover’s dream ruckman. If he wasn’t using his powerful, brick-like fists to thump the ball and gain as much territory for his team as possible, Polly was mastering the gentle tap straight down the throat of his rover, allowing for quick and easy transition football out of the centre.

Another method perfected by Farmer was to take clean possession out of the ruck and find a player forward of the contest with a booming offensive handball, which leads us to one of the most recognisable legacies he imparted on the game: the offensive handball.

“Never handball in the backline, only punt when you see a head. Kick the ball long and strong, handball son, and you are dead!”

That was the way the game was played, a fundamental rule.

Handball only to defend, you learnt it all in school.

Then there came this big man, blazing a trail from the West.

He came with a reputation, they say he was their best.

Graham ‘Polly’ Farmer, did come from over West.

Graham ‘Polly’ Farmer, with the double-barrelled fist.

“I know your reputation, but to me you’re just a hick. Now you’re in the Big-V, we brought you here to kick!”

He handballed long this big cat, as long as some could kick.

Geelong will always remember the man with the iron fist.

Graham ‘Polly’ Farmer, did come from over West.

Punch that football Polly, with your double-barrelled fist.

Graham ‘Polly’ Farmer, did come from over West.

Punch that football, punch that football, punch that football Polly, with your double-barrelled fist.

Recorded in 1981 by Mike Brady, Big Gun From Over West was an ode to a champion. It also serves now as a timely reminder for later generations just how the game was played then, and the mentality behind their tactics. It is no stretch to say that Polly Farmer invented the use of the handball as an offensive weapon. Before himself, as alluded to by Brady, the handball in Australian Rules Football was used out of desperation for a quick disposal whilst under tackling duress when a kick wasn’t a viable option. It is well documented that Farmer set a precedent and changed the way we play football by making the handball a tactic for moving the ball forward quickly.

Being a perfectionist, he would wind the window of his HR Holden Station Wagon down half way and use it as a target to practice his handball accuracy. He realised early in his playing days that the ability to win the ball quickly and dispose of it efficiently were more important than the method of your disposal.

“As a youngster, I realised I was big and not-so coordinated, and I found it easier to handpass than to try to evade players and kick. Perhaps I (also) handballed more than others because I understood that as a ruckman I had more opportunity to get the ball than most others”.

His teammates have since revealed that instead of just bragging of how many kicks they ended up with, it was unofficial team practice to keep a tally of the number of handballs they received from him. Another revered trait that Farmer possessed, often overlooked as time went on, was his constant assistance to young teammates on the field. If he knew he had younger, unestablished players around him, he would go out of his way to get the ball in their hands and get them as many possessions as early in the game as he could.

I played that way [because] I was a team player. It didn’t worry me if I had 15 or 16 handpasses, which don’t stand out as much as kicks, because winning is the most important thing. – Graham ‘Polly’ Farmer.

At the conclusion of the 1967 season, after suffering a narrow grand final loss to Richmond, Farmer would leave Geelong and return to play in the WAFL. To the surprise of many, he made his return not to play for his past side in East Perth, but as player/coach for arch-rivals West Perth. He would oversee two premierships in his four seasons at the helm, both coming against his former club, and he would take out yet another best and fairest award in 1969 before retiring at the end of 1971.

An eight-team, interstate premiers carnival was organised in his honour to recognise and commemorate his career and contribution to football in Australia. It was a career that saw him finish with a total of 356 club games -176 with East Perth, 101 for Geelong, and 79 for West Perth. He would also play 31 times for Western Australia, including games at four interstate carnival series, and five times for the VFL.

It was always said in his time at Geelong that like a cork on the tide, Polly would return to coach the Cats once his playing days were through. This was the case in 1973 when he was appointed as senior coach, taking the reins from Bill McMasters. Not being able to hastily replicate his great onfield success as a coach, Farmer fell victim to the notorious infighting at Geelong at that time. His coaching record fails to demonstrate the direction in which he was taking that team and ultimately pales in comparison to his extraordinary playing career.

Given the right resources and the time to build the team in his way, he was confident he would’ve been able to make a premiership team out of Geelong once again. This wouldn’t be the case as members of the board staged a coup and had Farmer ousted as coach, to be replaced by Hawthorn star Rod Olsson. Many in the football world now agree that had Geelong given Farmer the right chance, anything could have happened. But it was not meant to be, and his coaching record at Geelong was something that would haunt him deeply for years to come, such was his desire for success and his passion for the game.

“They knew the bigger picture and that their people were depending on them. They paved the way for the rest of us who came after them.” – Michael O’Laughlin (Former Indigenous AFL Player)

In 1971 Farmer would make history, becoming the first (AFL/VFL) player to receive an imperial honour, becoming a Member of the British Empire (MBE). He was also approached by

former Geelong player Neil Trezise about representing the Australian Labor Party in the seat of Corio, to which Polly declined and was quoted saying: “Apart from my commitment to my family, footy was the only thing I was interested in. So in my desire to succeed, I did all the things I had to, to do that.”

In 1994 the Polly Farmer Foundation was launched. Its aim was to provide opportunities for young Aboriginal people to make the most of their own skills in the sporting and academic arenas. Farmer wanted the foundation to be of practical assistance to young Aboriginal people with potential to do something with their lives. Not just sport, but in the professions and business. He wanted to develop links with the tertiary institutions and make sure Aboriginal people became leaders. Chief Patron of this foundation, Ernie Dingo has only immense respect for Polly and what he managed to achieve, not only for himself, but for the Aboriginal people of Australia.

Farmer met his future-wife Marlene in 1956. They married in 1957 and had three children, Brett, Dean and Kim. In the 1992, he and his wife sold their house and purchased a motel in South Perth. They ran the motel up until the late 90s when they fell on financial hardship; a drop in tourism lead to a lack of business and left the couple with no money or assets.

They refused to borrow money. Polly was quoted saying, “We have nothing and we are back to square one. But we didn’t borrow money to keep the business going. All my life I have helped myself and there is no reason why I can’t still do that.”

They were given temporary accommodation until two fundraising events organised by Sam Newman, John Watts and Bob Davis raised over $120,000 in a trust fund for Polly and Marlene, and a small villa was purchased for them.

1997 would see the $400m Northern City Bypass in Western Australia named the ‘Graham Farmer Freeway’.

“Dad considered himself lucky to be welcomed and accepted into football at a time when the Australian government was controlling every aspect of Aboriginal life.” – Kim (Daughter of Graham and Marlene Farmer)

Many varied reports have emerged throughout the years of instances of racial vilification that Farmer was subjected to. Many of his former Victorian teammates admit to still being unaware of any such abuse on the field. He admitted to some that he was the victim of vile abuse for many years on the field, however he took a tough stance of ignorance and never let the words put him off his game. If anything, they only proved a spark of provocation to perform at his very best. “I never took any notice of it”, Farmer was quoted to say. “I think anything that was said out on the field was to put people off, but it didn’t break my concentration and when I was called names I’d look at myself and say to myself well I can’t see it. It never worried me. I still was called ‘You boong, you nigger.’ That was understandable because you do anything to try and put people off their game. I didn’t go out of my way to chase people and thump them because they called me a boong. There would always be the chance to run through a bloke, knocking him down worked better than words,” he said.

“I was on another planet when I ran out there, no matter what people would say, they were never going to put me off.”

Despite his refusal to let such vilification affect him, Farmer also openly admitted that the Australian government failed in its treatment of Aboriginal people. “One of the great problems with all ways of life is you have a pecking order and the pecking in Australia has always seen that the Aboriginal race has been at the absolute bottom. Everyone else who comes to Australia is above the Aboriginal.” Farmer said.

“It could’ve been worse, they could’ve called me by my middle name” (Vivian)

– Graham ‘Polly’ Farmer.

One of the most sought after Australian Football cards is from the prized 1963 Scanlens set, and is none other than the card of Polly Farmer. There are multiple conspiracy theories amongst collectors as to why this card is so scarce. Ranging from the discernible; being such an enigmatic player, even back in 1963 this card was the envy of the series to children and collectors alike. To the controversial; the card of an Aboriginal Australian held less collectable value than that of a white player in 1963, the resulting discrimination lead to smaller amounts of his card being kept and saved. To the more popular urban legend; from the large sheets of card that these smaller cards were cut, his card was in the far bottom corner. It was common in that era for current paper processing technology, that such a card placement would end up being cut incorrectly. As the blade came down it would take too much off the edge, meaning quality controllers had to discard more of his card than anyone else’s. The latter being the more accepted version of events amongst collectors today.

The name Graham ‘Polly’ Farmer will be forever etched in the annals of Australian sport. Not only one of the greatest footballers our country has ever seen, but as one of the greatest sportsman in general. His contributions to the game are still evident in each game we watch, he revolutionised the way we play as well as paved the way for future generations.

Farmer’s long list of achievements are testament to the person he was, the support he gained and the unwavering commitment he showed to each and every task he took on in life. Adored by those that knew him and those who didn’t alike, you’ll be hard pressed to find a more coveted individual in any sporting text book in the land.

He was a pioneer, he was a ground breaker, he was a trailblazer, he was a revolutionary, he was Graham ‘Polly’ Farmer.

Hey, you know we have memberships here at The Mongrel, right? We are small, we’re independent and we’ve knocked back cash from the gambling industry as I reckon I’d be a massive hypocrite if I complained about all the gambling ads on AFL coverage and then sold out to them. For 40-80c per day you get access to our wingman rankings, defensive rankings, weekly player rankings as well as members-only columns and early access to my Good, Bad and Ugly evening game reviews.

Plus you help us grow. Come on… click the image below and help an old mongrel out.