A Moment For The Wind

For better or for worse, the wind was the protagonist of last night’s game. Main character energy. The most dominant performance in an AFL game since the last game The Launceston Wind played in.

For the first half, the wind favoured end saw 11.15 scored to 00.4. That’s 81 points to 44. It made a joke of the non-wind-assisted end – an absolute mockery. For the first half of that game, the wind provided a bigger advantage than a subcontinental pitch in a must win test match. It was a bigger advantage than picking Oddjob in N64 Goldeneye. It’s a bigger advantage than the umpires gave the Bulldogs in the 2016 Grand Final, I say through one eye. Anyways…

The wind infiltrated every facet of the game. When you play with it, you get an extra ten metres on your kicks and it advantages teams who love to run and play on the break, which can be both of these teams. When you defend with the advantage of the wind, you stay in front and try and force the other team to kick it long and over you, often leading to a swirling ball.

Watching the first half of this game was watching two teams try and solve this puzzle. The first quarter you see GWS taking advantage of the good conditions but you also see Hawthorn learning what they need to do in the third quarter, when they find themselves in this position again. It’s a test of tactical and positional versatility that these two teams feel uniquely suited for.

The other thing about the wind is that it it’s doubly advantageous to the team attacking with it when combined with the 6-6-6 rule. As play goes on, it’s natural to throw a man behind the ball to try and prevent goals and shore up the defence. When a team scores, the numbers are reset and the scoring team is given another opportunity to strike while the iron is hot, giving them the chance to create a self-perpetuating hot iron. This was most clear in the second quarter when the Hawks really started to run up the score, kicking four in six minutes through Weddle, Newcombe, Watson and Moore, to vanish the quarter time deficit.

My favourite thing about watching these two teams is their versatility, which I think is indicative of where the game is going. It’s very rare that all 18 of these players will be in their listed positions, because Adam Kingsley and Sam Mitchell both run game plans that allow for freedom of movement with squads positively chock full of Swiss army knives. It’s particularly evident out wide, with listed Hawthorn wingers Amon and Battle interchanging with Weddle, Morrison, Impey, D’Ambrosio, Day, Moore, Watson; and GWS wingers Callaghan and Coniglio alternating with Ash, Whitfield, Jones, Daniels, Greene. Being able to play this kind of horses for courses strategy, or be able to strategically overload, or just put a bloke in an unexpected position to sow confusion, is something that these two squads are at the absolute forefront of. Hawthorn also have an embarrassment of riches in the en vogue swingman role, being able to deploy Hardwick, Weddle, Battle, Sicily at either end to really cause match-up nightmares.

The Hawks’ penchant for mess and confusion defined their third quarter, and if felt like that infected the Giants game plan. The pressure the Hawks were able to create in their forward 50 created panic among the GWS defenders, and that panic led them to hack kick it out and seemingly trust that the wind would get them out of jail. You can see the logic here – play the territory, keep the ball away, hope that the chaos benefits you eventually. But this kind of chaos isn’t a zero sum game.

Bear with me here as I get a bit silly with it, but when you ping pong a ball into the forward 50, the ball is limited by the boundaries and the density of players. The Hawks plan to flood players forward and maximise opportunities works because most outcomes are beneficial – Hawks player gets the ball, Giants player gets the ball, ball goes through for a score, ball goes out and you get another chance at it.

Three of those four are Good Outcomes for Hawthorn. When you hammer the ball out of defence, likely to a 50/50 contest, even with the advantage of the breeze, the outcomes aren’t as beneficial. Best case scenario you nail the kick, get the ball, run the other end and score. This happened zero times in the third quarter. The Giants scored two in as many minutes and then were scoreless until a Stringer behind right at the end of it. The worst case scenario is an immediate turnover and giving the Hawks an opportunity to reset and whack whack it inside 50 again. The median outcome is that the ball goes to no one and bounces unpredictably on the ground, which may or may not benefit you due to its nature.

If you’ll permit the detour into abstraction, GWS getting sucked into a game plan that relies at least in part on the bounce of the ball felt like a big reason that their transition game fell to shit in the third and arguably took their best chance at the game with it. That fifteen minute scoreless stretch in the third felt like the game killer. Good for Hawthorn, as although they weren’t scoring, they also weren’t conceding in a quarter where they had the environmental disadvantage. Bad for GWS as they failed to capitalise on kicking with the wind.

Hawthorn’s first goal of that third quarter is a perfect example of how to create a goal in these conditions. The Hawks moved the ball down the ground straight from the bounce – interrupting some GWS momentum – and flooded into the 50 to force a mismatch. The entry goes to Ginnivan, who gives it to Impey, who kicks it wide to a leading Hardwick. At this point there are eight Hawks in the forward 50, and all Hardwick needs to do is beat his man and find an option. He combines with D’Ambrosio to cook the less mobile Himmelberg, faces infield, and finds Jack Gunston who’s been left alone at the top of the square while Buckley tracks the seemingly more dangerous Chol.

In short, you get around the wind by keeping the ball low and being patient. They created half a chance by getting the ball to the top of the 50 and seized on it by creating confusion, forcing GWS defenders into making a decision, and exploiting the ensuing mismatch.

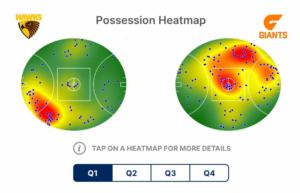

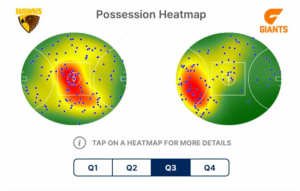

It’s Sam Mitchell’s acknowledgement of, and commitment to, this tactical versatility that made this third quarter happen. As an example, look at the possession distribution in the first and third quarters

In the first quarter, Hawthorn were hemmed into their defensive 50 as they reacted to GWS’ early barrage. In the third, the distribution was substantially more even, if not tilted somewhat in their favour, as Mitchell adapted to what it meant to play into the wind.

Hawthorn’s gameplan, at least as I understand it, seems to rely more on the players within the structure rather than quote-unquote ‘individual brilliance’, and for that reason I was really impressed by Nick Watson. He seemed to grasp what the game needed of him quicker than most, playing as an incredibly high half forward in the first quarter and a traditional small forward in the second. in the first quarter, he used his pace to run into the wind when kicking was less effective than expected, and whenever he got near the ball his football IQ stood out. It’s the kind of game that makes you think the Small Forward tag could be somewhat limiting for the player he may go on to become.

Early in the game, Jesse Hogan looked back to his Coleman-winning best, and looked like he could singlehandedly change the aerial calculus. There’s a lot of talk about Old School Tall Forwards being a dying breed, but while Jesse Hogan’s still crashing packs and making life this easy for the ecosystem that relies on him being himself. He had four, could’ve had six, somehow only took four marks but felt like he was a threat every time the ball got in his airspace.

It felt like there was a tacit acknowledgement on the commentary that these teams will see each other in a final. If this is a preview of a final, there are still heaps of relevant takeaways – how each team’s modularities stack up against each other, the week to week development of Callaghan and Day, Meek v Briggs, both of these team’s weird commitments to chaos. Even if you take the wind out of it, this was a fascinating game that is likely to inform heaps of what happens for these teams moving forward, and both are well placed to do so with coaches who love to adapt.