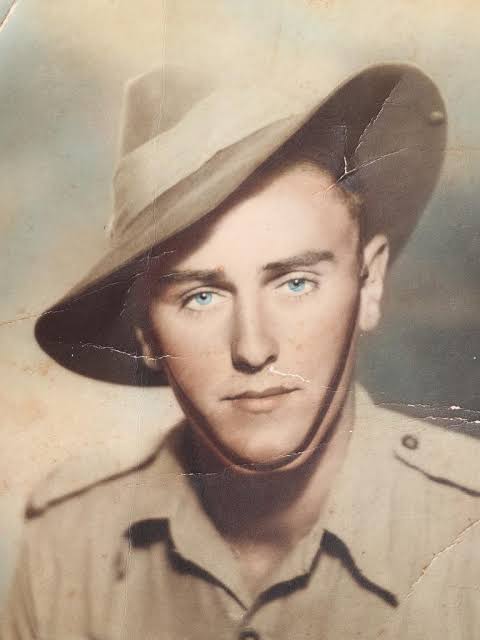

With Anzac Day fast approaching us, let’s take a glance into the life of a man who never considered himself a celebrity, and a man whose name isn’t common household knowledge.

But it should be.

The story of Jack Jones is one of Australian legend in both the fields of war, football, and our way of life. A true story of resilience and determination.

Born in Ascot Vale on the seventh of November, 1924, John Raymond Jones, known to everyone as Jack, was the fifth child of six. Jack recalls his father being an avid football fan, often tuning the wireless in to listen to the games being broadcast, and regularly hearing the screams and cheering of the Essendon faithful first-hand, living just around the corner from their home ground, Windy Hill.

One of his earliest memories as a boy was also one of his fondest. At the age of eight, his father asked him for the first time if he’d like to go to a football game. This took Jack by surprise, even as a child he was consciously aware of the scarcity of money and the fact that most children didn’t attend football games in the 1930’s for a number of reasons, one being that they just weren’t big enough to be able to see anything. He promptly told his father that he’d love to go, to which his Dad boasted of a new recruit that Essendon had playing on the team for the first time that day, a young man that many at the time were saying was the best player that the club has ever recruited – and how right they were. Jack’s father took him to Western Oval (now known as Whitten Oval) for Essendon’s first game of the 1933 season, a game where they’d witness the debut of none other than Dick Reynolds.

As his memory serves him, they stood out on the wing, as there was no way they would’ve afforded the scarce seats in the only grandstand. The detailed memories of that day may have faded from his mind, but one thing that he never forgot was the hysteria and excitement buzzing around the neighbouring suburbs at that time, just the sheer elation at how good this young player Reynolds was going to be, such was the socially inclusive aspect of football in tightly knit suburban communities back then. In later years, Jack would liken the idolisation of Dick Reynolds by all Essendon locals to Don Bradman. It’s funny to think that it would only be 17 years after that game at Footscray that Jones would win a third premiership playing alongside Reynolds.

Jack attended St Mary’s school in Ascot Vale until late in 1938, captaining the school football and cricket teams, when as a 13-year-old he decided that he no longer wished to attend school, preferring instead to find a job and enter the workforce. The problem was that the law required any student to be a minimum of 14 years of age before they could leave school to find work. Knowing of his personal desire to begin his future, he recalls a Nun telling him that no one will ever know, and allowed him to exit the school prematurely.

He found work soon enough as a messenger and merchant for a local barbershop, where he earnt 8s 3d (eight shillings, three pence) for a 48-hour week that involved advertising and selling different hair products for men. His next job would be one in an industry that he went on to spend decades involved in throughout different stages of his life. He took up an apprenticeship as a butcher in Northern Essendon where his weekly wage rose to 1£ 2s 5d (one pound, two shillings, five pence) for an often 60-hour week. Whilst juggling his apprenticeship and helping out at home, Jones was also playing football for Ascot Vale/St. Mary’s in the YCW competition until he turned 18.

Whilst listening to the radio in 1939, Jones heard Australian Prime Minister Robert Menzies announce that Australia had entered World War II. His initial feelings were of worry for his older brother-in-law, that he might have to leave his sister and family to go to war. A couple of years passed and tragedy struck, Jack’s father passed away, leaving him and his siblings to help their mother make ends meet. It was only 10 months after losing his father that Jack, himself, was called up to fight at age 18. Although he was one of the few that had the option not to serve because he was an apprentice to a trade, Jack didn’t know this at the time. Regardless, he was eager to go off to war because all of his mates were joining the army, most of whom were only a few months older than he was. At only 18 years of age, Jack Jones received a letter requiring him to go and receive a medical check and present himself to his local Defence Force Registry. On December 15th of 1942 he was enlisted in the Second AIF. He passed the physical and would make his way to Royal Park (the current site of the Royal Children’s Hospital), where The Australian Army headquarters for recruitment was.

Looking back on his decisions as an older man, he conceded a deep feeling of guilt and selfishness for not staying home and helping out his mother.

After signing up, his first port of call was to attend the Watsonia Army Barracks. It was here that they learnt about hand grenades, machine guns, water bombs, artillery, tanks and other components to war that Jack had never witnessed first-hand. He recalls sitting in the open park, where the instructors would show you a training aid gun or a dummy grenade, explain what it was and how it worked. He distinctly remembers the first time he held a Bren gun, the same weapon that he’d carry with him for the best part of the war. It was a strange time, not knowing anybody made the first few weeks feel isolated from the world that he’d grown up in. It wasn’t until they transferred to the Canungra Army Base in South East Queensland that he was made part of the 24th Battalion. This would be the first time that he had ever left the state of Victoria. There was a feeling around the base that they would all be shipped to the islands of New Guinea to carry out the arduous treks over all of the mountains, largely due to the 30-mile marches that the men had to do for training each and every day.

“You just did what you were told.” Jack shared. Once their training at Canungra was completed, they were transferred to the Townsville Barracks and before they knew it, this group of young men were aboard the transport ship Duntroon.

To what destination, they didn’t know.

After three and a half days at sea they waited for a navy vessel known as a Corvette to escort them through the open waters, zig-zagging in front of them as a security measure against the Japanese submarines. Jones, along with all the others slept in the hull of the ship, where rows upon rows of three-level bunks were situated, measuring only 18 inches wide with the bottom-most bunk sitting about 6 inches off the floor. Jack remembers hearing and feeling each heavy crashing of the waves on the side of the ship whenever it was rough and choppy.

It was far too long ago to remember exactly how many days they were at sea, but before they knew it, they were pulling into Port Moresby in New Guinea. With their gear promptly loaded in their packs, they received their orders to climb down rope ladders from the ship and onto 20 or 30 odd barges that took them to shore. They looked across at the mountains ahead of them, so tall that the clouds obscured their tops. One soldier turned to Jack and said “Now I know why we did all that training up in the hills”.

“You dropped the front of the barge and you had to charge onto the beach and into the jungle. Luckily there were no Japanese there waiting for us, so we arrived on the beach with no one getting killed.”

It was then that the assignment reformed together and set up a base on the beach, camping there and going on periodical patrols consisting of nine people: a Lieutenant, a Sergeant, a Corporal, a Lance Corporal and about five others, the aim of which was to head into the dense jungle in search of any Japanese soldiers.

In his own words, Jack explained that a battalion consisted of about 1000 men, half of those were fighting soldiers and the rest were mortar platoons, signals, pioneers, colonels planning the war etc. The very last patrol that he participated in at Bougainville, as the war drew to a close, only had he and two other soldiers in it, such were the casualties of war that they just didn’t have the men left to send out any more.

“Strangers become your best mates. We lost 91 killed and 197 wounded from my infantry battalion. Other battalions lost 200 or 300 killed. We were lucky I guess, but one is too many, let alone 91.”

It was his first day on the island that Jack witnessed the death of a comrade that he had been training with at Canungra. A fellow 19-year-old that he hadn’t even learnt the surname of yet, but who now laid dead next to him. It became common practice after losing a fellow soldier on a patrol, they would clear an area of about 30 metres and put a tripwire around the perimeter with a hand grenade in between two sticks. If the enemy came too close, they’d trip over the wire and the explosion would alert the battalion of an imminent threat. This usually bought them enough time to be able to bury their fallen.

It’s almost impossible to fathom in today’s day and age just what this generation went through. When placed on lookout detail, a pair of soldiers would dig a trench about three feet deep by a foot and a half wide, then take it in turns, serving two hour shifts through the night as lookout whilst the other attempted to sleep in the trench.

Attacks from mortar strikes were a continual threat. The enemy would have spotters up in the trees who would advise their units on the ground where to land the projectile explosives. This was a massive factor in the loss of lives on the island with many men killed during the mortar raids.

“You didn’t think about it, you’d survive the mortar fire but you didn’t know if you’d be alive by the end of the day. What could you do? I couldn’t be frightened because I had to look after the blokes around me. I never really felt fear at all.”

A few simple, unwritten rules that they always had to follow were sleeping with their clothes on, and never taking their boots off. If they happened to misplace their boots and were attacked, they wouldn’t have time to put them on and due to the spikes, shrapnel and vast undergrowth, they would never get far on the island without them. “Your boots were bloody heavy, but they were a bigger asset over there than your gun was, they saved a lot of people”, said Jones.

“Were you scared, no. It was just a job. People died beside you, in front of you, behind you, especially with mortar bombs coming over. You couldn’t hide from them. I didn’t have time to stop and think about fear because you had to keep going. I never thought of myself being a hero.”

Jack served 10 months on the island of New Guinea. Due to the rough, mountainous terrain, they had no tanks or vehicles, so defending the island was done entirely on foot. When asked what the food and eating conditions were like, Jack stated that they ate a lot of baked beans and simple, sealed rations because they were the safest foods to eat. After serving his 10 months fighting in New Guinea, his Battalion was withdrawn back to Australia, boarding the transport MS Van Heutsz at Madang to return home for two weeks rest and reorganisation, arriving back in Townsville in mid-September.

“Any of the really gruesome things, and there was a hell of a lot, you don’t want to talk about. You’re just all in it together in one bunch. It’s just like the football team running out on Monday. You have to play your part. And we had to play ours.”

He tells a funny story that upon his fortnight return home, his mother boasted that she had managed to get him something special for dinner to welcome him home (keep in mind that food was in short supply and heavily rationed due to the raging war), what did she pull out for his special dinner? A can of baked beans. He never had the heart to tell her that he no longer enjoyed them after surviving off them for 10 months. It was on his two-week break that he met a lovely young lady named Mary at the Moonee Ponds Town Hall dance, he had the pleasure of taking her out a few times before he left, headed to the barracks for more training before being sent to Bougainville. Luckily for him, he had asked Mary’s permission to write to her whilst he was deployed. Jack would go on to marry Mary in 1948 and share six children with her – Lynne, Peter, Brian, Tony, John and Anne-Marie

“I don’t think about it all the time but especially around Anzac Day every year you start to remember the blokes around you that got killed by a mortar bomb, or in a trench five yards away and he’s cut in half. You think about him and what his family are thinking today.”

Once his two weeks leave had drawn to an end, Jack rejoined his battalion for reorganising and training which took place at the Atherton Tablelands in Queensland, before leaving for Bougainvillea in April 1945. Jack would describe Bougainville as an island that was 120 miles long and 9 miles wide, between New Guinea and the Solomon Islands. They left Australia, bundled once again on a boat but with no idea of their true destination. Once they arrived it started raining in June and barely stopped the entire time that they were there. The main river was majorly flooded which meant they couldn’t cross to get over to the other side where the large congregation of Japanese troops had set up base. By the time the water had settled and they were able to find their way over, the atomic bombs had been dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, meaning that they no longer needed to cross as most of the Japanese had already begun their retreat after the country’s unconditional surrender.

“Thank god I wasn’t on Kokoda or I probably wouldn’t be here today. They lost huge amounts of people. If I were seven or eight months older, I would’ve been there most likely.”

Whilst waiting for the river to die down, there was a lot of downtime and training for the men. They carried out numerous fighting campaigns as they won back other territory from the Japanese and forced them further up the island. Bougainville was a completely different terrain from what they had previously experienced at Port Moresby. With more flat ground around them, they had more equipment in the way of tanks, bulldozers and tractors brought over. It was with the dozer that they cleared the grounds for their recreation and fitness, making a flat area for Australian Rules Football, Rugby, Boxing and even multiple Athletics Carnivals. Perhaps the most surprising was using the machinery to cut in a swimming pool and using water from a nearby creek pumped in to fill it. The story, as Jack told it, is that they acquired buckets of grass seeds from somewhere, and thanks to the humid climate with an abundance of heat and water, within 10 days they had thick tufts of grass sprouting on their new training ground. The land was largely torn apart from shell-fire and explosives, and because of the raging war there were no shops on the island. With very little to do in their downtime, a lot of blokes spent their time playing sports and keeping fit. It was this training that Jack credits for his own development as a footballer, being able to trace a lot of his future skills on the football field to the end-to-end kicking practice and constant pack marking that they did to fill in the time between going on patrols and carrying out objectives. A carnival was held between different units, where Jack would eventually hoist the trophy for overall best and fairest alongside fellow soldier, Frank Lazzaro, a centre player from Sale in Victoria.

“I was just lucky, the bullet or shrapnel didn’t have my name on it, yet the bloke standing next to you is gone, just like that. It’s just the luck of the draw.”

The first time Jack saw a tank in combat, it just happened to save his life. They were taking heavy fire from the Japanese at close range, it was the only time during the war to that point that he had been told to affix his bayonet and prepare for hand-to-hand combat. There weren’t many Australians there on foot, it was only one platoon, not the entire battalion. No sooner had they taken the order to prepare for close combat that a tank rolled in behind them and mowed down the entire attacking party, saving the lives of Jack and many other Australian soldiers.

“I often think of the Japanese, they had parents, they had a mother and father, probably had a wife and a couple of kids at home, they get here and we were shooting one another. It’s just not real. You didn’t think of it at the time because it was you against them. I didn’t hate them, I never have.”

One memory of football that Jack recalled from his time overseas was listening to the infamous ‘Bloodbath’ (1945 Grand Final between Carlton and South Melbourne) on the wireless, which was a very rare treat for them. When setting up their tents, it was common practice to dig a trench, roughly 18 inches deep directly below where you slept, so that you were below the ground level whilst sleeping. That way if any shrapnel or debris from mortar explosions were to occur whilst you slept, it would fly straight over the top of you. Jack was in the cook’s tent one night when a stray Japanese unit attacked his camp, blowing away the tent in which he should’ve been sleeping. If it had not been for the trench that he had dug previously, his mate that was in his tent would’ve been eviscerated.

After a number of tough campaigns over in Bougainville, the news filtered through on the wireless that the war was over on the 15th of August. Unable to know whether this was true or some sort of a ploy, it wasn’t until planes started flying over with “JAPANESE SURRENDER” painted underneath, whilst numerous planes dropped leaflets detailing the Japanese surrender and that the war was over. The battle didn’t end there though, as rogue Japanese raiding parties hadn’t heard the news and continued to attack for weeks after their country had surrendered.

“I’m bloody lucky to be here. A lot of my mates are still up on those islands.”

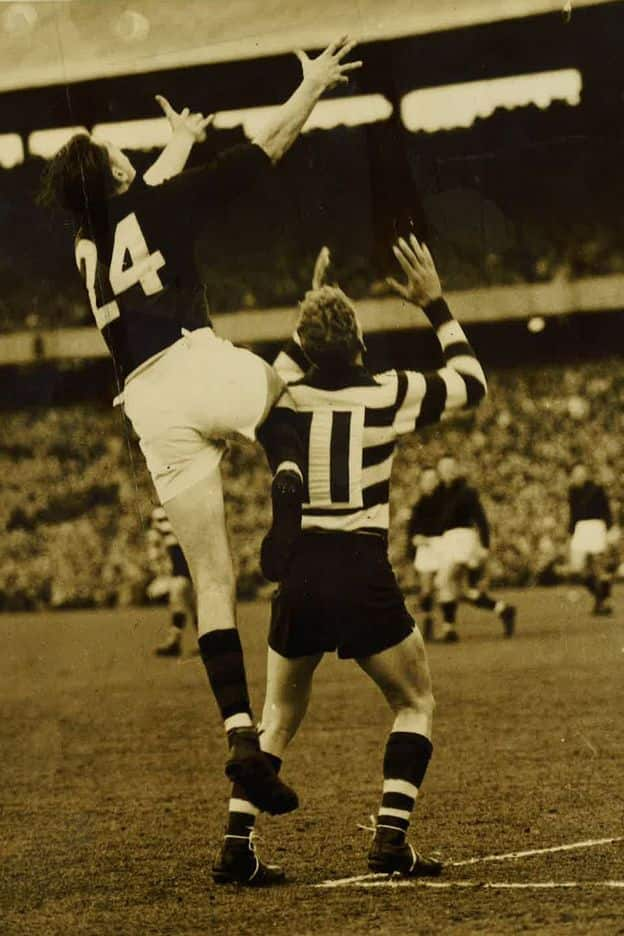

Due to the large number of ships sunk and destroyed during the war effort, it was a long and tiresome wait on the island for a ship to come and take his Battalion home – four days shy of three months to be exact. A lot of this time was spent on the football field for Jack, training, keeping fit and just waiting to get home. He happened to impress so many people with his athleticism and football ability that his mates in his Battalion told him that when he makes it to the big time, to wear the number 24 for them. He was one of a number of soldiers asked to take part in an occupational force to go straight from Bougainvillea to Japan and help them rebuild their country. Jack declined, saying that he just wanted to get home. He later admitted that he couldn’t stomach going over there as an occupied force to help the country get back on their feet when they were killing each other only a month before. A ship finally arrived and it wasn’t until the 12th of December that they returned to Australia and Lance Corporal Jones received his discharge on the 14th of March the following year.

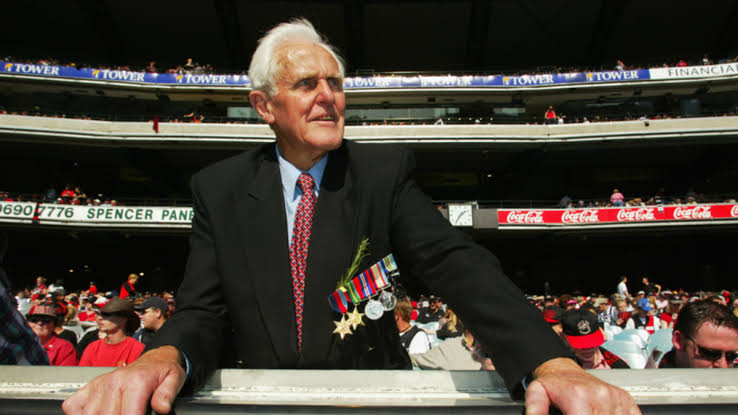

“Nowadays I notice the ‘well done, boys’ and, ‘thanks very much, boys’ and the praise comes out, particularly from young people. A lot of people with babies in their prams waving and saying thank you. You feel a bit proud that I did my bit to help.”

The day he arrived home he found his Mum waiting for him halfway up the street, because she had heard someone coming and couldn’t contain her excitement. Jack noted that the electric lights in the streets were all still covered, a precaution taken at night against bombing planes flying over. They spoke for hours before she remembered that there were three letters awaiting him from football clubs. “Who would want to write to me?” He quipped. Upon opening, he discovered that whilst he was serving overseas, clubs back home had heard of the football heroics he displayed in Bougainville before he had even returned to Australia. The first letter he opened was from Williamstown FC, the next from Brunswick FC (both teams in VFA) and the third one almost made him fall off his chair, it was from the Essendon Football Club.

“Why the bloody hell would they be writing to me?”

His first stop was a sentimental one at Williamstown because his father was born there and Jack barracked for them in the VFA. Former Collingwood player Ron Todd was at Williamstown after crossing over from the Magpies in a deal that saw him unable to return to League football for three years. Jack figured that since Todd had been in the Air Force, he would happily find a place in the team for a fellow returned serviceman. Alas, Todd had no interest in even speaking to Jack.

His second stop was Brunswick where a bloke named Ron Baggett was captain-coach, Jack knew him as the three-time VFL premiership player for Melbourne that joined the RAAF, and thought that maybe the fact that they had both served their country may buy him some more luck at Brunswick than it did at Williamstown. Unfortunately, this wasn’t the case as Baggett, like Todd, wasn’t interested in Jack either.

With the slightest sense of third time lucky, Jones headed off to Essendon, but with surprisingly little optimism. He barely considered himself good enough to play for a VFA side, let alone a VFL side. The thought of playing alongside his all-time idol in Dick Reynolds was still nothing more than a dream in his mind. Upon arrival he was seen to by a man named Bill Pierson. Funnily enough, Jack had gone to school with Pierson, and they had both served in the army and been stationed in New Guinea together. Luckily for Jack, Bill was more than happy to help him, even giving him a few hot tips before approaching the club. He told him not to show up early for the practice matches, otherwise, you’ll wind up playing with the rats and mice (untalented, lesser players trying out) and be lost in the crowd. Instead, he advised Jack to turn up late, that way he’ll be assured a practice match against last year’s senior players instead of fellow try-outs. If he was to go alright, he’d be a lot more likely to be noticed and the club would want to see him again.

Despite going against his every moral fibre knowing that he wasn’t showing up on time, Jones did exactly as he was told, and boy did he impress in his practice matches exponentially. Out of 100 players trying out, only two ended up being good enough. It was the next day in the newspaper on Monday the 15th April that Jack read ESSENDON RECRUIT JONES SHINES – he had made the cut.

Jack thought: “How easy is this!?” The newspaper two days later read: “Jack Jones, a serviceman, is a strong ruck possibility or a defender. They like his style.”

Once news circulated around the clubs that Essendon was signing a new boom recruit, Jack Pimm, Collingwood full forward and yet another returned serviceman that knew Jack from New Guinea, unsuccessfully attempted to convince him to try out for Collingwood, but Jones’ mind was made up. He never thought he’d be good enough to play in the seconds, let alone the senior team. He wasn’t giving up his dream of playing for the team he loved for anything. Besides this, he was zoned to Essendon after growing up in Ascot Vale and playing under 18s there, he just never considered himself a good enough player for those zoning rules to apply to him.

Jack was invited to a club dinner the night before the first game of the 1946 season when they made the team announcements. Sitting there in awe of those around him, he completely missed the majority of the team selection. It wasn’t until the bloke sitting next to him whispered in his ear “that’s you Jack, you’re in!” that he realised his ultimate dream was to become a reality.

Three days after reading his name in the newspaper, Jack would play his first game for his beloved Essendon. When offered a surprisingly low guernsey number (preferable to most at the time) Jack requested the number 24, keeping the promise that he had made to his comrades to wear the number with pride in memory of them. It was the 20th of April and he would make his debut in front of approximately 26,000 fans at Western Oval against Footscray, just as he had witnessed his Idol Dick Reynolds do 13 years prior – and like his idol, Jack too lost his first game of league football. Because the MCG and Lake Oval were still unavailable due to being used for the war, more games were being played at the smaller suburban grounds. He recalls his father and about 20 of his cousins being there at the game that day.

Jack went on to play the first eight games of the season, winning the next seven after losing his first. Beating South Melbourne, Melbourne, Hawthorn, Fitzroy, North Melbourne, St.Kilda and Richmond before he fell ill after contracting malaria. Now, there’s some terrible irony here. The entire time that Jack was stationed during the war, they were given a tablet daily to take in order to prevent them from contracting the potentially deadly malaria. So many men around him were unlucky enough to contract it whilst serving, but Jack himself never did. He always thanked the fact that he took his tablet daily, religiously, because he’d seen first-hand how crook those around him got. But nevertheless, three months after being home, he too fell ill from the mosquito-borne virus.

It would be two weeks before Jack got back into the side, that’s how long it took him to recover from his diagnosis. In his absence he missed a win over Collingwood and a loss to Geelong, followed by 8/10 victories, including winning the 1946 VFL Grand Final against Melbourne. Jack recalls the training sessions leading up to the Grand Final as being a massive spectacle with thousands of locals and supporters crowding Windy Hill to get a glimpse of the team. So his dream as a boy eventually came to fruition as he ran out onto the ground, led by his longtime idol, three-time Brownlow Medallist and now captain-coach, Dick Reynolds. Jones would be named a reserve for the match (to sit on the bench and only come on to replace an injured player) and he didn’t come on the ground until the final quarter, playing about 20 minutes of game time. After the win, the players celebrated in the clubrooms at Windy Hill until past 3 AM, Jack notably drank lemon squash all night as he wasn’t an alcohol drinker.

The Melbourne Sporting Globe newspaper of July 20th 1946 had a headline that read –

DONS HAVE STAR IN JACK JONES

The article then went on to say: ” To become a star with the leading League team in his first year of senior football is the achievement of Jack Jones, Essendon’s 21-year-old follower and forward. Jones is the fastest mover of the Dons’ four ruckmen, an excellent mark and good position player at half-forward.”

Across the 1947 season, Jack would be one of only four players to play all 22 games for Essendon, kicking 25 goals and only going goalless in five games. The club won 14 games and only lost five for the season before making finals where they would take on Carlton in the Grand Final, back in the days before they shared such a great rivalry. From all reports, Essendon led for the majority of the game, Carlton came hard late in the game when Norm McDonald, who had kept him to two touches for the day, allowed Carlton’s Fred Stafford a little too much room to move. With about 15 seconds left in the game, Stafford turned around from 50 metres and kicked a high ball over his shoulder on his non-preferred side that sailed through for a goal to put Carlton in front by a single point. The players sprinted back to the centre square and the siren went, crushing the dreams of the Essendon players. By his own admission, Jack was well held at Half-Forward that day, his first time playing solely in that position and he found himself at times playing opposed to Brownlow Medallist Bert Deacon who kept him goalless. The team had 30 shots on goal to Carlton’s 21. A feeling of letting one slip overcame the players as they laid on the floor back in the rooms after the game where no one spoke. Jack showered and returned home early, knowing that he had to be up at 5 AM the next morning for work at the butcher.

Essendon were a force to be reckoned with in the 1948 season, winning 16 of their 19 home and away season matches and finishing on top of the ladder as minor premiers. Jones would kick 26 goals for the season including a bag of five against Collingwood at Windy Hill in front of 30,000 fans and a bag of four against Geelong. It was also this year that he would marry his wife of 72 years, Mary. The same Mary that he had written to from Bougainville and taken to a game of football for their first proper date – Mary’s first-ever game. Leading into the Grand Final, they had won their last 12 games straight, including two games comfortably against their Premiership opponents, Melbourne. The Grand Final would go down in history as the first-ever drawn Grand Final in the VFL, and one of only three to ever occur. The scoreline of 7.27.69 to 10.9.69 remains to this day one of the biggest differentials in a tied game.

During interviews, Jack was always reluctant to divulge which Full Forward kicked 2.13 that day as to not embarrass him. Unfortunately for him, the newspapers back then didn’t hold the same sentiment, and with a little research, we know it to be their spearhead, and usually reliable goal kicker Bill Brittingham, who had barely scored 13 behinds with his tally of 39 goals for the entire season to that point. The following week they just couldn’t get near Melbourne in the replay, losing by 39 points, leaving the players to lament poor kicking in two successive losing Grand Finals.

During the week, Jack was still a butcher, earning a respectable 6£ 6s (6 Pound, 6 Shillings) for a 48-hour weeks’ worth of work, as well as an additional 3£ a game for playing at Essendon.

In 1949, Essendon would finish equal second on the ladder, but fourth overall thanks to percentage after winning 13 of their 19 games for the season. Jack would kick 20 goals for the season as he began to play more time in the ruck and occasionally at Half-Back, including a haul of five against Richmond. Jack described a standard game plan for him was to spend about 10 minutes per quarter in the ruck, and then head either forward or back as required. His ability to run at pace and for extended periods is largely thanks to the athleticism gained from training in the army. Essendon would take on Carlton in the Grand Final in front of 95,000 people, the club’s fourth in a row, and come out winners by 73 points, a then-record winning margin in a Grand Final. This was also the debut season of John Coleman who kicked 12 goals in his debut game and six in the Grand final, including his 100th for the season to take out the league’s goal kicking award (which would eventually be named after him).

Recounting his memory of the 1949 Grand Final, Jones tells a humorous set of circumstances that occurred on the day. For the Grand Final, each player received two tickets to get into the ground, one for yourself and one for a family member. Jack gave one to his mother and one to his wife Mary, deciding to pay for his own ticket when he got to the turnstiles upon arrival at the MCG. By the time he made it to the ground, his Gladstone bag on his shoulder bulging from having to hastily stuff his playing gear inside, every entry but the player’s gate was locked due to the game being a sellout. Carlton’s ruckman Jack ‘Chook’ Howell walked up and noticed Jones waiting at the gate and asked why he looked so worried, to which Jack told a lie and informed his soon-to-be opponent that he’d left his ticket at home. Howell insisted that Jones not worry about it, because he would help get him access to the ground. As Howell gave his own ticket to the steward on the gate, Jones heard him say “See that bloke behind me? I’ve never seen him before in my life.”

Once inside, Howell laughed and reassured Jack that he’d walk around to the Essendon rooms and tell them that he had left his ticket at home. Someone from the club eventually did get Jack inside, only to cop the ire of the club CEO for giving his ticket away. By the time he got in and got his gear on, he had to run out and take to the field.

It was an astounding sight to see, with fans sitting right around the boundary, hard up against the lines of play. Jack didn’t realise at the time, but the gates at the Ponsford Stand end had been broken down and by all accounts, at least 15,000 people piled into the ground without paying. It was during the first quarter that Jack approached the ball towards the boundary where he was pushed in the back by Carlton defender Jim Clark, sending him into the crowd of onlookers. Jack heard a familiar voice say “what are you doing here?”, He looked over and it was the voice of his younger brother of four years. Of all the 95,000+ people in attendance, he happened to land in the lap of his younger brother who had snuck into the game.

Spending more time in the ruck and at Half-Back during the 1950 season, Jones would kick 18 goals for the season from the 20 games he played. Most notably because a certain full forward by the name of John Coleman was doing the majority of the scoring in the team these days freeing up players like Jones to play a more versatile utility role, and players like Bill Hutchinson could focus more on their roving (even though it was nothing for Hutchy to score 50+ goals a season as a rover back then). Jack would marvel that he had front row tickets to the John Coleman show throughout his career, playing in roughly 97 of Coleman’s 99 career games alongside the champion that is widely regarded as the greatest full forward of all time. The Grand Final in 1950 would be North Melbourne’s first-ever since joining the VFL in 1925 and subsequently Dick Reynolds’ last game as captain/coach. It was all Essendon that day as they finished strongly to defeat North Melbourne by 38 points. Reynolds was chaired off the ground by awestruck supporters after the final siren sounded.

The 1951 season is one that resonates in the hearts of Essendon fans for all the wrong reasons. They would win 13 out of their 18 games and finish outright third on the ladder, with John Coleman again leading the league’s goalkicking for the home and away season. In the final game of the season, Essendon played Carlton and in a heated exchange, Coleman was fined and suspended four weeks for a strike in retaliation to provocation by Carlton defender Harry Caspar – colloquially known now as ‘the man that cost the Bombers a premiership”. Jones would note that the hit was very soft and that he knew something untoward had occurred to cause Coleman’s retaliation because he saw the incident first-hand, and it barely warranted a slap on the wrist compared to other events that happened that day. Coach Dick Reynolds had a hard battle convincing Coleman to return to the field after he stormed off in protest of being unfairly reported.

Despite Essendon’s appeals, Coleman was forced to sit out the entire final series. His side still made the 1951 Grand Final, albeit under a cloud of illness, injury and suspension to top players. Their number one ruckman in John Gill was forced out of the side with the flu, promoting coach Dick Reynolds to withdraw his retirement and name himself as 20th man to sit on the bench as a reserve player alongside future club legend, Jack Clarke, Reynolds felt that he had no other choice as all of his seconds players were tired and worn out from playing in the curtain-raiser earlier that day. Reynolds had little impact in his return to the field, Jack Clarke would later joke that if Reynolds had sent him on as reserve in the final quarter instead, then Essendon would’ve won the game. Geelong went on to win by 11 points.

1952 would be the beginning of a low period for the club, finishing out of finals contention for the first time since the end of the war. Winning only eight games for the season and ending a string of eight consecutive grand finals across seven seasons (including the replay in 1948). John Coleman won the league’s goalkicking award once again and Bill Hutchinson took home the Brownlow that year. Jones would only miss a single game for the entire season.

Essendon made the finals once again in 1953 but were bundled out in the first week by Fitzroy. Jones missed a couple of games due to injury and suspension, being moved to a much more predominant role at halfback that season. Once again John Coleman won the league’s goal kicking award and Bill Hutchinson was awarded the Brownlow Medal, making him a back-to-back recipient.

Finishing outside contention for finals once again in 1954, Jones only managed 14 games for the season through injury, an issue that plagued the entire team throughout the year, with Jones often thrown at Centre Half Forward to play right alongside the likes of John Coleman. He recalls one of his toughest assignments ever was playing on Mr. Football, Ted ‘EJ’ Whitten in the second last game of the season. 1954 would be another season that went down in folklore as a tragic one for Essendon, John Coleman had kicked 42 goals in only five and a half games, including bags of 10, 9 and 14. It was Round 8 against North Melbourne at Windy Hill where John Coleman would suffer a career-ending knee injury, robbing him the opportunity at playing a lengthy career, finishing up on 98 games for an incredible 537 goals. In later years, Jones would recall the incident as if it had only happened days prior.

Jack Clarke won the ball and came booming out of the centre, sitting at half-forward, Jones found himself thinking he had better make a lead to receive the ball from the incoming rover. A voice from behind him bellowed “that’s mine, Jona!”, Knowing instantly that it was the voice of Coleman, Jones made space for his full forward to lead at the ball and take the mark, noting that Coleman was the Field Marshall of the forward line and called all the shots. Coleman went up for the mark and landed awkwardly on his right knee, dislocating it in a tragic injury that ended his career prematurely. Although he and the club tried to get him back on the field over the next few seasons, he just couldn’t get his knee right.

“He was unbelievable. I honestly don’t think we saw the best of him. He wasn’t a brilliant trainer, but, boy, could he play.” – (Jones on Coleman)

At the end of the 1954 season, Jack Jones would call time on his own career, one that spanned 175 games, winning three out of the seven consecutive Grand Finals played by Essendon, one of only four players to do so, including a still active club record of 133 straight matches between 1946-1952 with the distinction of never having being relegated to play a reserves game in that time. He represented Victoria and was inducted into Essendon’s Hall of Fame in 2012, the club developed the Jack Jones Youth Academy for their younger players and after his death in 2020, the club would rename the cafe at their training facility after Jones, given he loved to frequent the facility and enjoy his cuppa and biscuits. During his time, he kicked 156 goals playing an array of positions including Half-Forward, Centre Half Forward, Half Back, Ruck and on both Flanks, being named Essendon’s utility of the year in five of his nine seasons and also best clubman – a true testament to his versatility as a player. He filled in as Vice-Captain for John Coleman regularly when Coleman would play state or carnival football, or was injured.

The answer to the question, who contacted Essendon whilst Jones was stationed overseas to tell them how good of a player he was, eluded Jack for over 30 years. One evening at an Essendon club dinner he was speaking to former player Ray Watts, who played 59 games for Essendon before enlisting in the Royal Australian Air Force. Ray asked Jack how he came to be on Essendon’s radar whilst serving. Jones responded that he never knew, nobody at the club could ever tell him. It was then that he copped a gentle elbow in the side, to which another former Essendon player that left the club to enlist, Les Begley said to him “Now you know.”, He turned to Les, puzzled, and asked him what he meant, to which he informed Jack that given he still had contacts at the club when he enlisted in the war, he had watched Jack play a lot of football in Bougainville first hand and had written the club a letter endorsing Jack and recommending that the club invite him down to train there upon his return to Australia. A mystery to Jack for over 30 years, now laid to rest.

Jones would name EJ Whitten and Bob Skilton as the two best players he ever played against and Bill Hutchinson, a dual Brownlow Medallist, as the greatest player that he ever played with, noting that his burst speed out of the centre, his ability to run all game and never tire, accumulate “upwards of 50 touches a game” and kick bags of goals regularly as a rover set him apart from everyone else – including his childhood idol, three time Brownlow Medallist and three time premiership Captain-Coach Dick Reynolds and champion full forward John Coleman, all of whom Jones played alongside. He would consider Hutchinson and Reynolds two of his best friends, even after football, and in 1982 Jones was chosen as one of the pall bearers to carry Hutchinson’s coffin at his funeral.

The career of Jack Jones was not over yet. Earning £8 per week to play for Essendon in his final season of 1954, at age 30 he began looking at opportunities elsewhere to further his career post-VFL. There is a story told of how Jones was returning home from a car trip late in 1954 when he and his wife Mary stopped in Albury, seeking accommodation for the night. Finding a vacancy at a bed and breakfast that happened to be owned by Jack Adams, a patron of the Albury Football Club. Adams recognised Jones and instead invited the Jones family to stay at his personal residence for the night, where they chatted about football and the current vacancy of the coaching position at the Albury Tigers.

According to newspaper articles from the time, Jones was refused a clearance to coach Brighton after being accepted as a playing coach. He was also headhunted by Moe with separate articles reporting that he had accepted a deal to head to Gippsland, also as a playing coach. In reality Jones had made his mind up already after receiving correspondence from Albury, that thanks to the kindness shown to him on his recent visit, after speaking with his wife Mary about uprooting their life and moving to the country, she said “Let’s go”. So, the Albury Tigers is where they went. It was quite common for ex-VFL players to be offered lucrative contracts to play or coach in the Ovens & Murray League, which was at that time one of the strongest country football competitions in the state.

The offer to play and coach Albury was £25 per week, over triple what he was earning at Essendon. The Jones family moved to Albury where Jack worked as a butcher in the main Street of town during the week and was captain-coach of the Albury Tigers on the weekends.

Upon arrival at the club, he was offered the prestigious number 1 guernsey, to which Jack respectfully declined and requested his sentimental number 24 in homage to his Battalion from the war, especially knowing that a lot of the blokes he served with had come from the Ovens & Murray area.

In his first season at the helm (1955), the club finished fifth and narrowly missed playing finals. With a midseason move to switch Jones from centre half back to centre half forward being hailed a masterstroke, Jack would lament their finish, saying that if they had made finals, their form late in the season would’ve been good enough to see them go all the way and win it.

His prediction ended up coming to fruition in 1956 as the Tigers would only lose two matches for the entire season, before they would comprehensively beat North Albury Hoppers in both the Semi-Final and the Grand Final. Jones was outstanding across the final’s series, with one newspaper heralding him as “the greatest thing to happen to the club in a long time”.

The 1957 season saw the Tigers make the Grand Final once again, this time against the Wangaratta Magpies. Jones would hold similar regrets to those of the Grand Final that he played in for Essendon ten years prior, suffering through yet another one that got away from him. The Tigers led for most of the day and held a strong, 27-point lead at three quarter time. There was less than a kick in it with a minute remaining in the game, when the Magpies forward, who had been well held for the day by all accounts, got free and snapped a winning goal with only seconds to play in the game.

Their fortunes wouldn’t improve in the 1958 season when they were bundled out of the finals, losing a wet and miserable Preliminary Final to Wodonga by only four points. The Tigers were confident going into the 1959 season, but midway through the year Jones suffered a horrific injury where he was kicked in the face, suffering damage to his jaw and a broken cheekbone. He would liken the injury to that of James Hird, who required facial reconstruction after a crushing blow left his face with many broken bones. Jack still suffered numbness and mild pain in his face for the remainder of his life, blaming the incident for a slight lisp that he would occasionally speak with.

Jack would finish his playing career at Albury with 171 goals kicked from his 75 games and won multiple country championships before taking the reigns as coach of the now defunct Kergunyah Football Club in 1960, which would eventually fold and become the origin for the Wodonga Raiders, before returning to Albury & District League as part of the Umpires Board for two seasons before he and his family moved back to Melbourne. Jack is now a Hall of Fame member in the Ovens & Murray Football League.

Jack returned to butchery once back in Melbourne, working for Gilbertson’s Meats for over 35 years, eventually getting into finance and management for the large company’s fleet of stores.

“I have red in one eye and black in the other,’’

In retirement Jack became a patron of the Melbourne Cricket Ground, running countless tours of the facility and sharing stories from his playing days. He kept a close relationship with the Essendon Football Club as well, still regularly doing tours at Windy Hill, hosting match day events and doing numerous motivational events for the players, especially in the lead-up to Anzac Day. One of Jack’s proudest moments in his later years was his task of taking the 1st-4th year players of the footy club to the shrine of remembrance in the days before Anzac Day. Telling of his own battles and instilling in them what was required of them as young footballers at a prestigious club, especially around a time that resonates in the hearts of so many Australians.

Despite always being well dressed and well presented, regardless of the function he was attending or the company that he kept, you would seldom ever find Jones inside a dining or function room once the siren sounded for the match. On more than one occasion I found myself alongside or not far from him out in the stands, looking as smart and respectable in his suit as most men of his age were, but none of that mattered once the footy was on – Jack was there to watch his Bombers play, and he did so from the comfort of the fold-down seats alongside all of the other screaming, passionate supporters, earning himself the eternal respect of the Essendon faithful.

There is no doubt in my mind that had Jack not played in a time where many of his teammates went on to be some of the best players that our sport has ever known, his name would be one that is instantly recognisable amongst Essendon and opposition fans alike. One thing that amazed me researching this article, was just how many newspaper clippings and articles from back in the 40’s and 50’s had titles and banners such as: JONES STARS with names such as Reynolds, Coleman and Hutchinson all getting much smaller mentions and press, not just on one occasion either.

In early 2020, Jack Jones was diagnosed with cancer and given 3-6 months to live, unfortunately passing away aged 95 on the 24th of March. A symbolic date given that the number 24 occurred so frequently throughout his life. From the year that he was born, to the number of his Battalion, to his playing guernsey number, to family member’s birthdays, anniversaries and weddings, to the date that he passed away, the number 24 will forever signify Jack Jones in the hearts of true Essendon supporters.

Due to the current global pandemic, neither the family nor the Football Club could offer Jack Jones the proper send-off that he deserved as a family member, ex-football player, club devotee and national hero. This year on Anzac Day, the Bombers will wear a special guernsey in his memory, adorning 24 red poppies as the sash, Jones’ infamous number that followed him throughout his life and career, as well as a numerical number 24 on the breast of the jumper in his honour. A terrific and timely gesture from the club.

An Essendon Football Club legend, an Australian football icon, a national hero for service to his country and a loving, caring family man. The story of ‘Gentleman Jack’ is one that I’ve taken great pride in learning over the years, and I take even greater pride in meeting him on numerous occasions and considering him an acquaintance.

Rest in peace Jack Jones.

Like this free content? You could buy Jimmy a beer, or a coffee, or something to trim his nasal hair as a way to say thanks. He’ll be a happy camper.